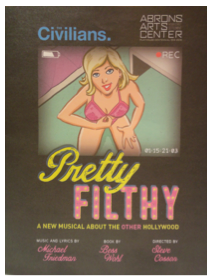

Leyla Vural is a current OHMA student. In this post, she discusses the use of the interview in the new musical Pretty Filthy.

At the risk of sounding prudish, I’ll admit that I know nothing about porn. I’ve never seen a porn film. They always struck me as offensive, just another way to exploit women and profit off of their bodies. No thanks; I’m not interested.

I am interested, though, in people’s stories. And as an oral historian, I like to see the myriad ways that interviewers take interviews and the stories people have told them about their lives and turn them into something long-form, engaging, and shareable. And so in February, I went to see “Pretty Filthy,” a musical about “the other Hollywood,” the one in the San Fernando Valley: the porn industry. The show is the latest work of The Civilians, which Zachery Stewart of Theater Mania describes as “the leading investigative-theater company in America.” “Pretty Filthy” is based on more than 100 interviews with actors, directors, agents, camera people and others in the so-called adult film industry. “Armed with their notepads and recorders, The Civilians… conducted interviews and visited sets to get an insider’s glimpse into a world that is far more than the sum of its (very) visible parts,” says the “Pretty Filthy” website of how the show came to be.

The result is a high school style musical. Eight performers play a variety of characters on a simple set. There’s the Midwestern teenager who dreams of being a porn star (the alternative is $7.20 an hour on the weekend shift at Hardy’s). There’s the middle-aged woman who asserts that getting paid for something she likes means “I’m not a whore.” There’s the agent who loves his “girls.” The stories the characters tell depict complex lives. Stardom doesn’t last. It’s difficult to move between sex as work and a romantic relationship at home. It’s getting harder to make a living in a rapidly changing industry. Going mainstream is not an option. Yet the characters challenge the idea that nobody likes being in porn, that nobody could like it, just as their stories challenge the notion that people in porn are living in the belly of the beast. There are no drug problems, no stories of childhood abuse, no evidence of anyone in the business treating the performers scornfully in “Pretty Filthy.” These are not victims, the show insists, nor do there seem to be any villains in the industry. Everyone is just pursuing a version of the American Dream.

Porn, it turns out, is segregated. There’s straight and gay, but also white and black. “Pretty Filthy” focuses on the straight, white scene. The rest of the industry peaks in just a bit: characters mention in passing that they “don’t do biracial” and one of the young guys, Bobby, segues into gay porn because it pays better. After a song the men sing about the difficulty of having to perform on demand (double entendre intended), the lone African-American in the cast comes on stage: “I’m sorry, is it hard to be a white man?” It’s a funny, biting moment before she describes her experience. She earns less than white women; she’s expected to do things white women won’t; she’s on the receiving end of a more lurid gaze.

As an oral historian, I was interested in the way the show includes the interview process in the story. Although the audience does not see interviewers, at times the characters speak to them. “Hey,” says Sam, the agent, “actually that could be a song” at one point. At another, he suggests leaving something he’s said out because it’s too sad. As the story turns to the rapid changes that the Internet is bringing to the industry, Becky, the Midwestern teen, appears on a big screen. She’s hosting an online live video sex chat room and the interviewer has come to the site looking for her with follow-up questions for the show. The audience does not see the interviewer, just what s/he types. When Becky thinks it’s a customer, the interviewer writes, “I’m actually from the thtre co? the musical? didn’t know how to reach U....srry…” The conversation ultimately angers Becky. “You want to tell a hard story,” she says, “but I’m okay.” I give the writer/interviewer credit for exposing the tension.

Often scorned or rendered invisible as people (flesh on the screen notwithstanding), “Pretty Filthy” sets the record straight: Porn stars and their industry colleagues are people, too. Art with a social purpose doesn’t always succeed as art. It can be too earnest. But “Pretty Filthy” works. It’s engaging storytelling, at times funny, at others poignant. On the night I saw the show, the singing wasn’t always consistent and there are elements of Broadway-style razzmatazz in the numbers that aren’t my favorite, yet “real” voices shine through. In an interview with Vice, Bess Wohl, the show’s playwright, talks about basing the show on real people. “Our goal was to make [the audience] feel like these are things that were actually said…There were places where we would base a character on a real person, and then find a piece of material that somebody else said that was also in that vein, so there was some blending and reassigning. But I feel good saying all of them are based on real people that we met.”

Interviewing raises ethical questions. Oral historians discuss this all the time. Alessandro Portelli describes an interview as an “experiment in equality” with interviewer and interviewee constructing the exchange and making meaning of it together. We hope that’s always the case, but as in all human interactions, there’s a power dynamic in interviews. Alexander Freund worries that it’s too easy for the interviewee to feel that the interview is an exercise in “coerced self-revelation.” In the Vice interview, Wohl is asked about how the people The Civilians interviewed feel about the process. “We thought a lot about whether we’re exploiting them,” she said. “We’re not paying them. What are we offering them? More “exposure”? But is our theatrical exposure different from the way they’re exposed in their professional life? What are the nuances of that?” Wohl and the rest of The Civilians concluded that “the answer was to let them speak in their own words, and give them their own voice. That felt like a way of putting them on stage without taking advantage of them.”

I still don’t want to see a porn film, but with “Pretty Filthy” I’m glad I got to hear people from the “other Hollywood” tell their stories, and sing about them, too.

I’ll also be checking out The Civilians’ new work. They’re the first theater company to take up residence at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.