Oral history and theatre have many natural intersections, performances crafted from interviews and then re-interpreted and embodied by actors. But what about a performance crafted from an unintentionally discovered piece of audio, whose narrators the creator has never met? In this post, OHMA student Caroline Cunfer considers how Alison S.M. Kobayashi implemented oral history-like practices in her groundbreaking performance, “Say Something Bunny!”

Almost two years ago, I ran into friends who begged me to go see a performance. “It’s called Say Something Bunny!” they said, “we don’t want to tell you anything else, but you have to go see it. And get there early so you can sit at the table.” A table? Who was Bunny and why weren’t they speaking? I wrote it down and told myself I’d see it in the fall when I was back in New York.

A few weeks later, my mom emailed me a New York Times article about the same performance. “This sounds so up your alley!” she wrote. Having dabbled in sound documentary for my undergraduate thesis, she thought I would be interested in a performance crafted from an audio recording. This was almost a year before I even knew that oral history was something one could do, and when I later reexamined my life through the lens of my newly discovered oral historian-ness, “Say Something Bunny!” was one of the first things that struck me as entangled in this discipline that I unknowingly had been moving towards for the greater part of my life.

“Say Something Bunny!” is a performance created by Alison S.M. Kobayashi and her partner, Christopher Allen, and is constructed from a found audio recording. Before I attempt to describe this genre-bending performance, I must first say that it is inherently difficult to describe. The difficulty in describing Kobayashi’s work is illustrative of its trailblazing singularity, and its inability to dwell within the confines of any pre-existing art form. Is it documentary art? Immersive theatre? Found-object art? Experimental theatre? Kobayashi manages to straddle all of these disciplines, pioneering an art form that vacillates between fiction and non-fiction, found and created, past and present.

The inception of “Say Something Bunny!” began with profound curiosity. In 2011, Kobayashi found herself in possession of a wire recording that had been passed through multiple hands after being found at an estate sale. This antiquated recording method, which uses spools of wire thin as hair to capture sound, held two audio recordings. The amateur recordings, Kobayashi would discover, were made by a young boy named David in 1952 and 1954, and documented two evenings in his family’s living room. They held a discordant chorus of voices thick with New York accents that layer over each other and are often unintelligible. There’s nothing apparently remarkable or important about the audio recordings; they feel relatively uneventful and quotidian. So ordinary, it’s as if to listen to them is to be eavesdropping on these characters. For a first-time listener with no context, it would appear nearly impossible to discern who was speaking, let alone to understand what was going on.

“And the wire recorder,” Kobayashi says towards the beginning of her performance. “Where is that? Why is this scene being recorded?” Driven by intense curiosity, and exhibiting valiant patience and close-listening, Kobayashi listened to the recording hundreds of times, yearning to understand who these people were and why this recording existed. And after six years of using cultural references and clues from the recording to guide her detective-like research, she was able to ascertain the exact dates of the recordings and identify each person speaking.

The result is an enthralling performance centered around the wire-recording and its transcript, each audience member “playing” the part of one of the people speaking. Although no actual performance is asked of the audience, participants are invited to inhabit a character for the night: the first time I was given the role of Lou, and the second time, Shirley. Kobayashi uses audience members— most of whom are seated at a round table that bears resemblance to a wire recorder reel— as reference points, often addressing them directly as if they were the characters themselves.

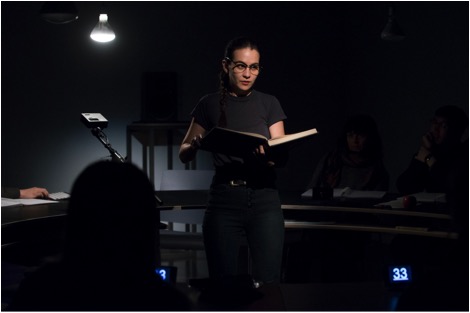

(©Henry Chan, The New York Times)

In her performance, Kobayashi explodes this outmoded found object and the family we hear speaking. “Say Something Bunny!” serves as an interpretation of this audio, and the understanding Kobayashi has excavated from it as she allows her research and imagination to give life to these characters. Over the course of two and a half hours, she brilliantly unspools the life and color of an ordinary family in 1950s New York, offering the audience insights into the vibrant social, cultural, and political realities of the time of the recording. She breathes vitality into an object that could easily have been tossed aside and deemed irrelevant or obsolete. She gives a second life to a family who unwittingly preserved themselves for posterity, and gives posterity the gift of encountering this family in a moving and animated way.

“Say Something Bunny!” is not inherently a work of oral history; Kobayashi did not engage in the dialogic, co-creative interview that is typically paramount to academic oral history practice. Yet as an oral historian, it is clear to me that in their conception of this performance, Kobayashi and Allen implemented critical and creative processes exemplary of oral history goals and methodology. Similar processes deeply inform my practice of oral history. Curiosity is often the force that drives us to encounter the minds of others through the intimate exchange of an oral history interview, and Kobayashi’s profound curiosity strikes me as similar to my own. Oral history is often described as “history from the bottom up”, oral historians concerning themselves with the narratives of “ordinary” people and their embodied experiences of history. Kobayashi’s ability to give great importance to this ordinary family and evening doesn’t seem far from this intention, as she places value on the “ordinary” human voice and experience that are central to oral history practice.

As an audience member, I found myself completely engrossed with and riveted by the palpable obsession, curiosity, and care with which Kobayashi treated this wire recording and its narrators. In oral history, we tend to speak of intersubjectivity as relating to the direct engagement between two people who are physically in each other’s presence. Kobayashi has never met all but one of her characters. Yet she was somehow able to create an unconventional intersubjective space as we witness her engaging with these strangers in a compelling and intimate way. As audience members, we have the feeling that she knows them, and intimately. Why else would she have spent six years poring through censuses, erotic films (this will make more sense when you see it), and college yearbooks? Her engaged work is exemplary of the potential for “personal” relationships to be fostered through secondhand archival interview access and analysis.

The secondary use of archived interviews is an ongoing conversation in the oral history world, some arguing that secondary oral history analysis unfavorably divorces the data from the labor, practices, and relationships that gave birth to it. Others view secondary access as a rewarding practice of re-examining and re-contextualizing data. Kobayashi’s performance convinced me of the possibilities of this re-contextualization and re-birth of “data”, despite her form of secondary data analysis straying from the traditional archival sense . She proves that rigorous secondary analysis of preserved sound can allow us to nurture relationships with people we’ve never met. Natasha Mauthner describes the labor performed by the interviewer, and how this labor cannot be disregarded, or detached from the interview—I would argue that although evidently of a different nature, Kobayashi engaged in a labor that has no less merit than that of the creator’s initial one. Mauthner fears the interviewer’s labor becoming invisible; Kobayashi foregrounds her “secondary” labor and renders it highly visible, creating a performance which unavoidably implicates her own research.

“Say Something Bunny!” is a beautiful illustration of repurposing a found object—which in the oral history world is translatable to the repurposing of archival audio—and of how we can expand our imagined possibilities of what this looks like. How can we explode and breathe new life into ordinary objects, and repurpose and re-examine found ones? How do we discover narrative in these objects? Can we give interviews another life?

When I saw “Say Something Bunny!” this year for a second time, two months into my oral history graduate program, I saw Kobayashi’s work in a new light. Her performance struck me as a rendering of annotation through performance, an annotated transcript come to life. Annotating a transcript is both a self-reflexive and intersubjective act, aiming to further interpret, analyze, reflect upon, and provide additional context for our interviews. Throughout her performance, Kobayashi accomplishes a similar objective. She interjects the audio with cultural references, discoveries, interpreted and recreated scenes, and explanations of her research to give the audience a richer context for and understanding of the circumstances of this audio’s creation. She also makes herself a character of sorts: she is our guide, and as we watch the performance unreel, we are simultaneously watching her relationship with these people take shape. This echoes the interviewer’s critical awareness of identity and relationship to her narrator in an oral history interview. Kobayashi rejects the “scholarly detachment” present in many history-making practices, and instead, like an oral historian, embraces her role in this work. As we watch and listen, we cannot remove Kobayashi and her experience of research and discovery from her findings.

There are many words in the oral history lexicon that illuminate this practice beginning with the prefix “inter”—interactive, intergenerational, interrogative, intertextual, intersubjective, interdisciplinary . Kobayashi and her newfangled, futuristic work of art embody most all of these. I’m not sure what Kobayashi calls herself, or if she’s ever thought of herself as an oral historian, or if that even matters. Perhaps all that matters is her impressive ability to turn the ordinary into the extraordinary, and that we have the privilege of not just bearing witness, but of also becoming entangled in the narrative ourselves.

Caroline is a member of OHMA’s 2018-2019 cohort and is thrilled to have the privilege of spending this year taking in and carrying strangers’ stories with her. Her thesis project explores the ways in which the November 13, 2015, terrorist attacks in Paris have had varying implications and impacts on people’s lives and well-being, including her own. Check out her work at OHMA’s upcoming exhibit Inter\views!