Pablo Baeza is a current OHMA student. In this post, he discusses the politics of being a witness.

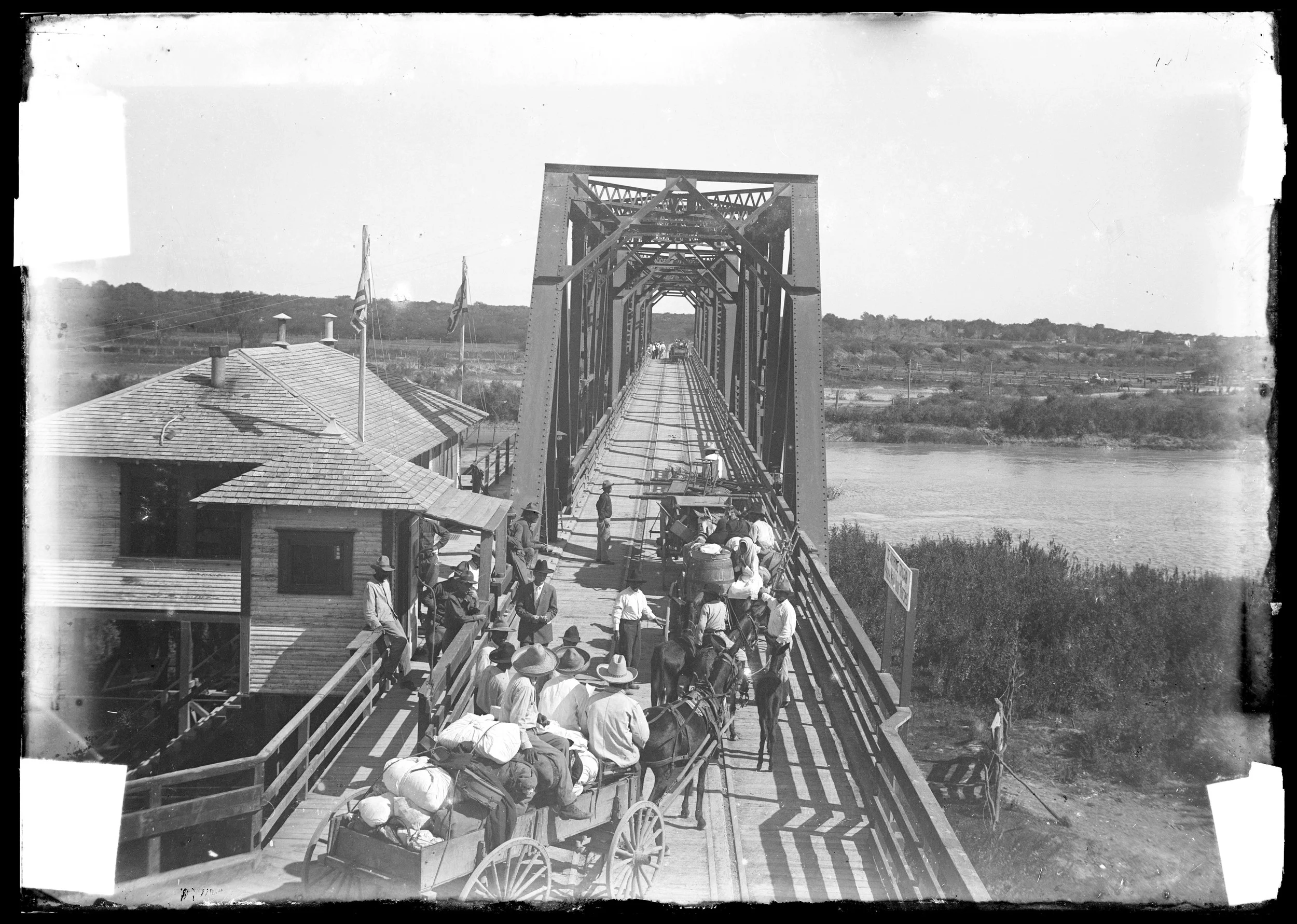

Refugees fleeing to Mexico over the Rio Grande due to border violence and persecution in Texas

As an undergraduate in college, I was an ethnographer on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, in San Diego and Tijuana. When I would return from the border to the small, private liberal arts college I attended, I would consistently get asked the same question – “Is it safe to go down there?!”

Patiently, I would always respond the same way, something like, “I’ve never had any trouble in Tijuana, and really appreciate the time I’ve spent there.” But I also tended to qualify my answer; “Tijuana’s safe for me. I’m a foreigner, I’m a bilingual Latin American, I can visit the city, be a researcher, talk to people, and come back to California at the end of the day. If I lived in the polluted slums of eastern Tijuana, would I feel safe? If I were an ex-factory worker’s child with nowhere to work in a city that needs narcotraficantes, that would be a very different situation.”

In short, being a non-Mexican Latino ethnographer moving between Tijuana and affluent Claremont, California made me think, not just about privilege and the way academics risk othering the communities they study, but also about the politics of being a witness. Who is safe on the U.S.-Mexico border? What is the history behind who is safe and who is not, and why? And what is our responsibility, as border scholars and historians, to make those politics visible?

Monica Muñoz Martinez, a border historian at Brown University, seeks to make border violence visible through public history in her native southwest Texas. Raised in small-town Uvalde, Texas, it wasn’t until Martinez studied her home state’s history in Providence, Rhode Island that she became aware of the role Texas state officials, including the famed Texas Rangers, played in the colonization, land theft and mass murder of Mexican national communities living in Texas after the U.S.-Mexican War. Her multimedia project, Refusing to Forget, focuses on a peak of racial violence along the U.S.-Mexico border in south Texas, from 1910 to 1920. In particular, she tells stories about the Texas Rangers’ complicity in the murders of Mexican residents and landowners in south Texas during the time, either directly or through lack of prosecution towards vigilantes. For example, on the project’s website, Martinez describes actions typical of the era in a way chillingly reminiscent of recent public cases of police brutality:

“On September 28, 1915, for example, after a clash with about forty raiders near Ebenoza, Hidalgo County, the victorious Rangers took about a dozen raiders prisoner and promptly hung them, leaving their bodies in the open for months. Several weeks later, on October 19, after a dramatic attack derailed a passenger train heading north from Brownsville, Rangers detained ten ethnic Mexicans nearby, quickly hanging four and shooting four others. Cameron County sheriff W.T. Vann blamed Ranger Captain Henry Ransom for the killings. Vann took two suspected men from Ransom and placed them into his custody and likely saved their lives. Both proved to be innocent of any involvement.”

Martinez’s project seeks to challenge the way Texas border history is traditionally told, acknowledging the lived experiences and intergenerational traumas of Tejano border families. This year, Martinez and her colleagues were able to assemble an exhibit at the Bullock Texas State History Museum, highlighting the stories of families who had experienced violence at the hands of vigilantes and Texas state officials. When describing the opening of the exhibit, Martinez talked at length about the power of being able to create a space for educators, border residents and those new to Tejano history,to come together to engage with the material and publically recognize the need for new curricular resources and education about the border in Texas – and to advocate for the teaching of history that acknowledges the history of border imperialism. Martinez even described the opening of the exhibit as a space of catharsis for families impacted by border violence, able to connect with each other and even reunite with old friends and family members.

Additionally, Martinez’s website provides a space for her many audiences to learn about the history of border violence in Texas, for those whose lives have been affected by border violence to share their stories, and for individuals to learn more about her project and its development via project information and an active, well-maintained blog. Though the website does not yet contain access to border oral histories, one can only hope that a well-curated collection should become available as a next step in the project’s development.

Martinez’s project is a model for public historians hoping to stimulate dialogue about U.S.-Mexico border politics. Its multimedia accessibility, which combines web content with exhibits both mobile and housed at powerful Texas cultural institutions allows for an audience both global and local, with varying degrees of familiarity with the history she tells. Its focus on making the history of colonization on the U.S.-Mexico border visible through oral history allows the project’s many audiences to engage with how a history of violence is remembered in the present by border residents. Lastly, the project’s commitment to transforming the landscape of Texas history education by advocating for curriculum reform and providing educational materials has the potential to change the way Texans experience history, despite the politically contentious nature of border history. Ultimately, Martinez’s work, by refusing to forget, fully engages the complexity of the border region to ask still-relevant, fundamentally crucial questions about how border residents live today.

The Rio Grande, separating Texas from Mexico