In this article, Fanny Garcia (2016) reflects on her path to oral history through her family’s journey to naturalization, her experiences with xenophobia, and the recent Central American refugee crisis that spurred her mother to share her story.

I’m in New York City right now during a blustery night in late September and I wish I was sweltering in the dry heat of Las Vegas. Not because I miss it but because on this same day, my mom is going to her U.S. naturalization ceremony.

She and I started the journey towards sanctioned U.S. citizenship together. In 1986, my mom and I arrived in the United States as undocumented migrants from Mexico. I became a citizen in 2008 and my mom also applied for naturalization that same year, but she didn’t pass the citizenship test. This same year, the fee increased to almost $700, making it hard for her to resubmit her application. While I went on to cast my first vote as a U.S. citizen for Barack Obama, my mom’s application stalled. It would be nine years before she could try again.

Fanny and her mom, Maria Polanco.

I was proud to cast my vote for our first Black president, but this wasn’t the only reason why I decided to become a citizen. I was scared. As I watched the 2008 presidential election year unfold, xenophobia and nativism increased and millions of legal residents like me felt that we were the targets of anti-immigrant sentiment. The birther movement, for example, questioned that Barack Obama was a natural-born citizen of the United States simply because he complicated the idea of who should be president. Obama wasn’t white, his middle name was Hussein, and he had lived abroad as a child. Also, included in this birther movement ideology is the fringe theory that Obama was a “secret Muslim,” and people said “Muslim” like it was a bad thing.

Ironically, my citizenship and “Voto Latino” helped elect a president that has deported more than 2.5 million undocumented immigrants (many of them Central Americans) during his time in office and by the time his term ends, will be the president that has deported more people than the sum total of nineteen presidents who governed the United States from 1892 to 2000 combined, according to government data compiled by the Department of Homeland Security.

All this, plus the Obama Administration’s failures during the ongoing Central American Refugee Crisis, increased my commitment to recording and preserving the contributions of undocumented Latinos, especially Central Americans. I believe the best place to start is with your own story. After all, how can you ask other people to talk about their lives if you’re not comfortable discussing your own?

After graduating from UCLA last year, I packed my entire life into a U-Haul truck and moved to Las Vegas. One of the things pushing me towards the desert was my desire to conduct oral history interviews with my mom. I wanted to ask her what was it like growing up in Honduras. Did she miss it? What was the pivotal moment that made her leave and come to the United States? Did she consider herself a U.S. citizen? How strong were her ties to Honduras after living here for so long? There was so much to do, but getting my mom to agree to an interview was tough.

There’s a saying in Spanish, “Un gran error es arruinar el presente recordando el pasado”—which translates to, “It’s a mistake to ruin the present by remembering the past”—and my mom lives by this dicho. For her, the present and the future are the only things that matter. The past should be forgotten. Part of the reason she believes this is that she carries a lot of shame about the way she grew up. Born on a finca, a banana plantation, to a peasant family in Honduras, my mother grew up poor for most of her life. It wasn’t until she left home to strike out on her own that she gained some financial independence. My mom avoided all discussion about her childhood, so I learned to not ask her about it. Realizing that I might lose her trust if I used a life history approach and started asking questions about her childhood, I asked instead about all the people around her when she was growing up. Eventually we got around to talking about how my birth altered the course of her life forever and prompted two trips to the U.S., both as an undocumented immigrant.

My move to Las Vegas put me in the crosshairs of the type of xenophobia that inspired the birther movement. Shortly after arrival, I realized that I was no longer in the progressive bubble of sunny Southern California where micro-aggressions like “all Latinos look alike” are common. They happen so often that I’ve learned to shake them off and discuss them only when I’m in safe company, among people who understand and will have some of their own experiences with micro-aggressions to share.

What happened to me in Las Vegas was more in line with what the Anti-Defamation League calls “alt-right” or Alternative Right, a term used to identify a growing number of people, emboldened by the politics of Donald Trump and others, that centralize the dehumanization of people with different skin color or non-Christian religious preference. One woman told me I had no moral compass or conviction because I did not believe in Jesus and insinuated that I was not the right kind of American because I favored universal healthcare. “You want everything given to you and you just got here. My family has been here for generations and I’ve had to work hard for everything I have,” she said. The effect of this xenophobia on my personal and professional well-being was so intense that I began to search for ways to mobilize and fight back.

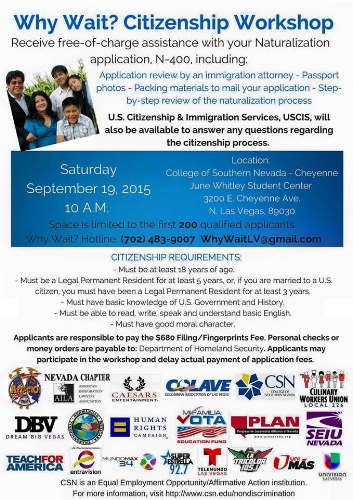

I joined forces with Progressive Leadership Alliance, Nevada (PLANevada). Their Organizing Director, Astrid Silva, a tireless advocate for DREAMers and an undocumented immigrant herself, invited me to volunteer at a citizenship fair. The goal of these fairs was to provide comprehensive assistance and education about the U.S. naturalization process to countless legal residents who qualified for citizenship. I was trained on how to fill out N-400 Applications and encouraged my mom to apply for citizenship again. This time she could do the citizenship test in Spanish because anyone fifty-five years of age or older can take the test in their native language and with the assistance of an interpreter if they have also lived in the United States as a legal resident for fifteen years. Furthermore, my mom was able to pay for the cost of submitting the application through a grant provided by PLANevada.

PLANevada’s Citizenship Fair Flyer from September 2015. This is the fair my mom attended and where she was able to receive assistance with her N-400 application.

Inadvertently, she became a spokesperson of sorts for the citizenship journey. Hers matched many stories we were hearing from the applicants—that they had been eligible for citizenship for years but were just now submitting their paperwork. My mom was able to speak with various media outlets including the Las Vegas Review Journal, The Guardian, and Uprising with Sonali.

By far the interview closest to an oral history approach was the one she did with Megan Messerly, reporter for the Las Vegas Sun. I provided translation from English to Spanish for my mom and it took place at my apartment. Messerly began the process by asking a simple question, “Where do you want to begin?” The question allowed my mom to open her story wherever she wanted. She started in 2014, when the Central American refugee crisis began. The sight of women and children who were not much younger than she was when she made the same journey with her own daughter affected her deeply, even more so because news reports showed the U.S. government’s rejection of Central Americans as refugees and asylum seekers. It made us question our identity as Central Americans and citizens in the United States.

Thirty years after arriving in the United States as an undocumented immigrant, mom becomes a naturalized citizen. September, 2016.

Messerly wrote, “Polanco said she was moved to apply after seeing the way the United States had handled the surge of Central American children into the country in 2014, saying it reminded her of her own story. Polanco came to the United States in 1986 with her 9-year-old daughter, Fanny, who was suffering an acute form of bronchitis. Doctors in Mexico City, where they were living at the time, had told Polanco that if she didn’t get Fanny to the United States for treatment, the girl was going to die.”

My mom’s story echoed the thoughts and motivations of many Central American undocumented migrant women today—they are mothers who don’t want their sons and daughters to die. Thousands of women and children are fleeing widespread violence, organized crime, femicide, government corruption, and impunity that threaten their lives every day. The media’s coverage of the crisis has largely focused on the cause and effect of the situation and the quantitative data that tells the public who and how people have been detained and deported. Yet, it rarely asks how people feel about their displacement: what it means to them individually, and what it means for their families and communities. Oftentimes, the subject’s internal struggle is glaringly missing. Oral history provides the narrator control of their story and allows the public to look within, at the meaning derived from the story they choose to tell.

My goal as an advocate for marginalized communities and as an oral historian at OHMA is not to insert myself into the stories of Central American refugees. My Central American story is completely different. I was lucky to have come to the U.S. in the ‘80s when times were different and the journey to the U.S. was less harrowing. However, as Hondurans now living in the United States, my mom and I could not remain silent. With our citizenship and our vote, we want to say to Central American refugees, “Aunque el gobierno diga diferente, usted también merece vivir y prosperar en los Estados Unidos.” Even if the government says otherwise, you, too, deserve to live and thrive in the United States.

Fanny Garcia is a graduate student in the Oral History Master of Arts program at Columbia University. She is OHMA’s 2016 Merit Scholarship Award recipient and winner of the Columbia Oral History Alumni Association’s 2016 Student Record Fund. Fanny’s research will examine detention center documents and asylum testimonies in comparison with oral history interviews. In her analysis of these different texts, she aims to shed light on the traumatizing impact of detention center procedures and asylum application process on Central American refugees. Check out a short clip from her Memorias Perdidas, Mejor Pulidas project.