By Sach Takayasu

What was it like for patients during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic if you were Asian, Native American, or “Other?” Who fought on behalf of this voiceless community? What were some of the battles? Sarah Shulman’s ACT UP Oral History Project inspired Sach Takayasu to explore these questions. Hear the answers in her oral history interview with the legendary activist, Suki Terada Ports.

Scroll to the end of the article for full transcripts of each audio file.

Columbia University’s Oral History Master of Arts (OHMA) Workshop (10/21/2021), Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP, NY 1987–1993, featured Sarah Shulman, whose oral history interviews, book, and film gave voice to numerous activists whose efforts in fighting HIV/AIDS had previously been ignored by the mainstream media.

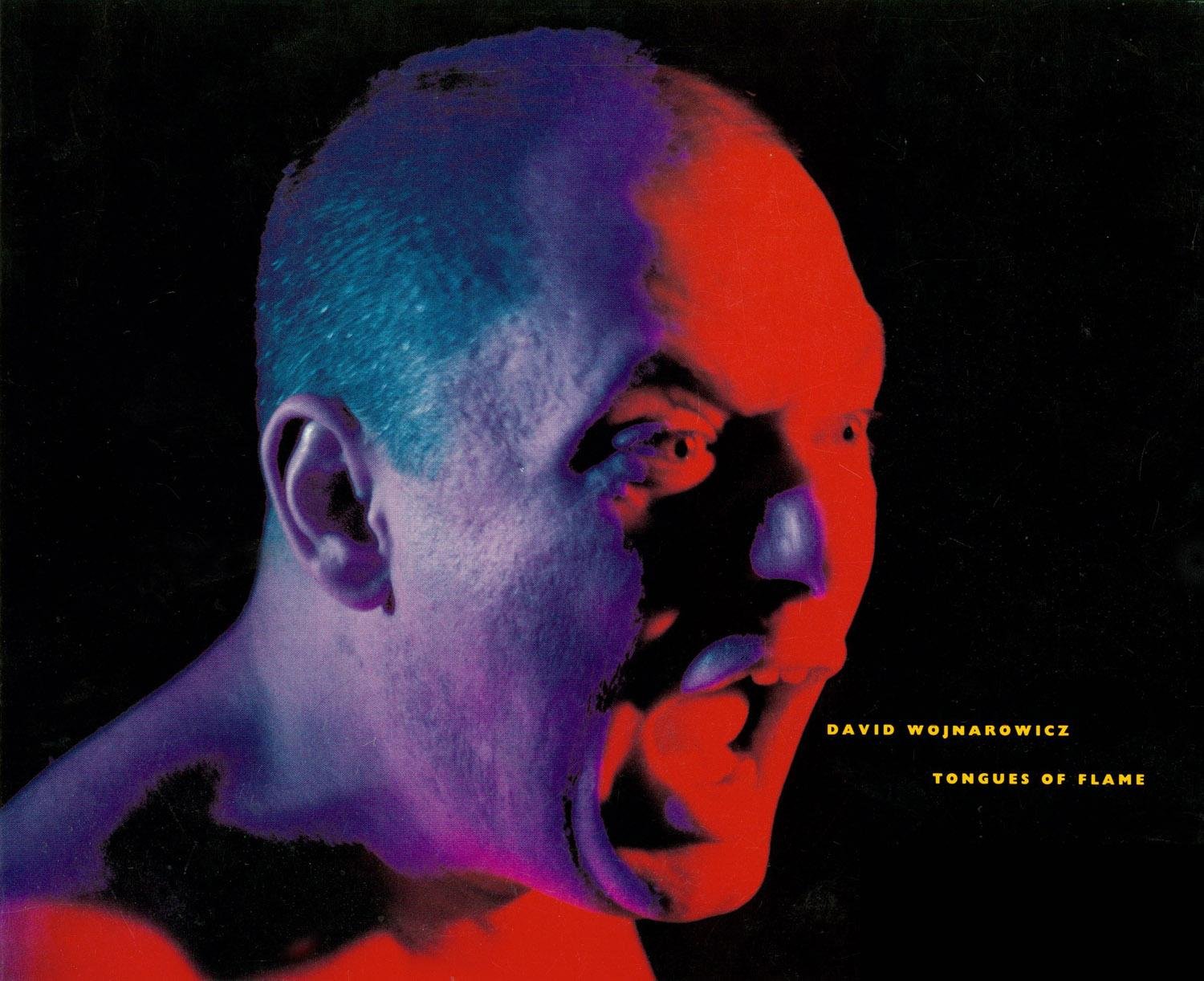

A poster of David Wojnarowicz’s exhibition, Tongues of Flame. A face of a man with an intense look, with his mouth open as though he is shouting. The face is red on one side, purple on the other, the hair green, against a black background.

Source: https://galleries.illinoisstate.edu/images/exhibitions/1990-wojnarowicz-tongues-of-flame.JPG

In Ms. Shulman’s The ACT UP Oral History Project, several narrators refer to David Wojnarowicz, the artist/poet, as one of the key inspirational figures in their activism. In January 1990, still vibrant and at the height of his career, David came to the University Galleries at the Illinois State University for Tongues of Flame, an exhibition of his works. The director, Barry Blinderman, introduced me to David who greeted me warmly. Unfortunately, lacking social skills, I was unable to engage in a meaningful exchange with him. I always regretted this. 18 months later, David died of AIDS.

Fast forward to today, I am learning in OHMA, those skills I lacked. As though by fate, my first project was interviewing an HIV/AIDS activist, a legend in her own right: Suki Terada Ports. It was like being given a second chance.

Suki and I engaged in our oral history interviews at the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University, OHMA’s partner in this project. Born and raised in New York City, she shared moving stories about the impact of WWII US policies on her family, her lifelong dedication to education, and activism. This post presents some of her reflections on how the epidemic affected a diverse group of people and her efforts to help them. The themes she touches include:

Obstacles in preventing and treating HIV/AIDS

Overlapping issues of language, class, education, history and culture

Food pantries’ assumption about the food needs of a diverse community

I hope you will be inspired by this small glimpse into her arduous journey.

So the local community took action.

One of the causes of this disbelief was the dearth of reporting on how HIV/AIDS affected the various minority communities. Reporting was not possible because back then, data on this population was not collected. Suki talks about what this meant.

Take for example this 1975-1981 CDC form, in contrast with the most recent 2020 census, which disaggregates population data in much more detail:

Suki’s tireless efforts garnered her numerous awards but she highlights one in particular.

Suki mentions that addressing this structural issue, together with the Native American community, took a very long time. Yet the community still faced numerous challenges.

Then there was the issue of languages.

Cultural challenges also surfaced in something as fundamental as food. Food pantries assumed food preferences did not vary across culture and ethnicity.

Tackling these overlapping issues necessitated establishing an enduring entity.

Suki was fighting a war which demanded perseverance, a quality she possessed as a lifelong educator. She not only educated the community, but also policymakers—over and over.

The hard work of Suki, her community, APICHA, and ACT UP, produced significant progress in the fight against HIV and AIDS. However, challenges still remain according to Suki:

“There still are many families throughout the world who don't know about HIV and AIDS because they don't know about their transmission or they don't know about the actual virus.”

And this includes the US, where HIV/AIDS continue to affect many, including Asians, whose number of HIV diagnosis has increased in recent years. Some of the issues raised by Suki persist. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists “cultural factors” as one of the prevention challenges: “Some Asians may avoid seeking testing, counseling, or treatment because of language barriers or fear of discrimination, the stigma of homosexuality, immigration issues, or fear of bringing shame to their families.”

This post merely scratches the surface of the issues and Suki’s efforts, but was written in the hopes of creating a fuller understanding of what this epidemic meant. I encourage the readers to learn more about the works of Suki and Sarah, starting with some links in the “Resources” section below.

Sach Takayasu is a degree candidate in Columbia University’s Oral History Master of Arts program and contributes to the Weatherhead East Asian Institute’s Oral History project. She served as the inaugural Fellow and an interviewer on the Obama Presidency Oral History Project.

Source of all the audio recordings:

Suki Terada Ports oral history interviews, 2019; OHMA Fieldwork Partner, Sach Takayasu; Japanese American Women Oral History Project; Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University.

Resources:

OHMA Workshop Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP, NY 1987–1993 (recording)

Suki Terada Ports (video): Nakazono, Stann. 2017. Suki Terada Ports.

University Galleries of Illinois State University, Tongues of Flame

Written Transcripts for Interview Clips:

-

In 1981 when the AIDS epidemic started, people began hearing something about an HIV virus, and they used various doctors and information to find out a little bit about it, but most people were not too interested in it because they didn't think it affected them. It was a disease that was thought of as a problem affecting gay white men.

Eventually by 1984 or 85, there became more people infected with this disease. And so people in New York started wondering what was going on with various people having a disease that nobody seemed to understand what was going on.

It was critical that people in minority communities, whether it was black or Hispanic or Asian or Native American, that people should understand what was the problem, how it was transmitted and that it could affect anybody, depending upon the activities that they did, either had the transmission of infected blood or sexual transmission.

-

When they decided to have this project started and they started the Minority Task Force on AIDS (MTFA), The Reverend [Robert L] Polk [founder] asked if I would coordinate the activities that were going on with this program and get people to learn about this, and so we started a program. And at first, it was very difficult because a lot of people didn't believe that this was a disease that could affect people of color because they had never heard about this disease. So, we had to do a fair amount of education. And the education was met with some resistance, one with the people of color who themselves didn't believe that they could be exposed and get this particular disease that they had heard was only affecting gay white men.

-

Getting to get people to understand about AIDS was one thing, but it was also a problem that many Americans don't know the difference between Asian groups. So we had a major problem that statistics were listed as White, Black, Hispanic and Other.

Now, the Other was because a lot of people didn't understand about who the Other was. So you have the two largest groups of different peoples. Native Americans had over 500 nations, so you had different tongues, different languages, different customs, different tribal issues. And then you had over 20 Asian and Pacific Island groups. You had these two largest groups put together in a set of statistics called Other. And so nobody understood really the importance of breaking down that.

So a group of us, some Asians and Native Americans, went to the Secretary of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and the Office of Minority Health in Washington. And we said to the Secretary of Health and the head of the AIDS programs for the Centers for Disease Control, Dr. [James O] Mason, “You've got to change your statistics. You've got to change the recognition of the issues of this disease.”

And so they agreed instantly and said, “Sure. All it really means is adding another column.” So they made a column for Black, White, Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander and Native American. And then there was finally a last column called Other, which was people who somebody had not, had failed to get what their racial ethnic background was.

So it was really, quite an important change in the way that statistics were gathered, but the reason that it was important was because there was another column: Doctors and people taking down the data about people.

A patient would come in. They would have to ask them, Where are you from? What is your racial ethnic background? They couldn't just say, Oh, you’re Other. They had to ask, Are you Korean or are you Indonesian? Are you—. Where are you from? Or are you from Choctaw native tribe or you—. What group are you from?

And so eventually there became a recognition of different peoples so that people of color became less faceless than they were originally.

-

One of the awards was the Native American Leadership Commission on Health and AIDS, the Native American leadership response to HIV and AIDS. We worked together, and that was very special to me because we went together to get the Secretary of Health to say, “Yes, no more Other” and we got Asian Pacific Islander and Native American. So that that was very special.

-

I think, HIV, this particular virus has caused more problems because it overlaps issues of language, of class, of education, of even history.

There were issues that were a matter of coming out, so to speak, that were not commonly discussed. I'll just share, for example, Asians, and I will specifically say Japanese because I'm of Japanese ancestry. One did not easily talk about sex. There was, I mean, I was— my parents found me in a blueberry patch. That's how I was brought into the world. But if you have a disease which is transmitted through sex, and your particular racial history/ancestry does not easily talk about sex, then along comes this disease that's transmitted by sex. If you're going to teach somebody about the disease, you're going to have to talk about sex. And people were not comfortable doing that.

So you first have to have people comfortable talking about the method of transmission. And then how that method of transmission is affected by a particular virus, which is going to get into the bloodstream and which is going to affect somebody. You have to freely talk about this. And if it's not a comfortable subject—the source of transmission— and you're going to have people who are going to be reluctant to talk about it. And in some cases, angry—they don't think it's appropriate. And certainly, it's not appropriate for a man and a woman to be talking about sexual transmission if you're not comfortable talking about sex to begin with.

-

One of the issues that developed was you have people who speak different languages. And if you are going to teach somebody about a disease and you speak English and the person you're trying to teach speaks perhaps Chinese or Japanese or Korean, or perhaps is from one of the over 500 Native American nations or over 20, 30 various Asian or Pacific island ethnic [groups]. If you're going to talk about a disease and how it's transmitted, you have to be pretty specific and you have to be pretty accurate. And it doesn't happen if everything is taught in English.

If you're from one of the Asian countries and you're uncomfortable talking about sex to begin with, then you're talking about a language that is totally different if you're from Indonesia and you have a doctor who is going to talk to you in English. It doesn't help you at all to learn about a disease that if you do X or Y, you could get a terrible disease, or if you're a woman who doesn't speak about sex comfortably. But also, there are some differences in words used by women and words used by men in some Asian languages.

And therefore, you could totally miss the point on how a disease is being transmitted if you don't really understand the language, let alone some of the differences between words that a woman would use and words that a man would use. And so, there are many differences and expenses involved.

And a doctor wants to warn you about this disease and talks to you in English, and you don't have the foggiest idea what that doctor is talking about because he's using a language that you don't understand. And so this developed into a major problem so that people of color were at a major disadvantage in learning about AIDS. And therefore, the numbers of cases grew very rapidly. And both men, women, babies developed a disease which partly happened because doctors or nurses or community group leaders didn't understand the difference between Asian languages, let alone the difference between when you're trying to expose somebody to understand about a disease and you don't understand that a Chinese person doesn't understand what a Korean person is saying. Just because you have an Asian face, that doesn't mean you understand the language. And the same with people who were on Native American reservations or who came out of a reservation and lived in a city or town, but had originally learned a native language.

-

If you have a group in East Harlem that has primarily people who are Hispanic. Somebody in the family gets AIDS. You have to be able to explain to the pantry group that you need to have the whole family have food that is beans or rice or combination of food that would be something that the whole family would enjoy eating and not just the person with it. So you had to have various lessons in the language of the people who were distributing the pantry bag. Each time, it's over and over again. Not only are you talking about the symptoms, but you then now talking to somebody in a food pantry that people who are of Hispanic background, people who are of Japanese, Chinese, Indian—you have different food preferences. And you have to start all over again, educating people about the food preferences and the people who are infected by a particular disease and who may have problems—issues of diarrhea or problems and issues of X or Y or Z. And you need to explain it in the language that the person understands and teach the person how particular food that you're eating could be infecting your ability to feel better by eating the kind of food that you're used to.

You have issues that have to do with whole families’ food ability. And is a problem that was not easily accepted because there are a lot of people who think, Well, everybody should like hotdogs and hamburgers and, you know, French fries or whatever. But that's not the case. There are a lot of people who have different food preferences. So food pantries had to be very often re-adapted for the people attending them.

But add on to that, they had a particular disease that affected them in certain ways, and you felt better if you had rice or you had whatever that was not only a kind of food that your particular racial ethnic group liked, but also made your stomach feel better. So you had a lot of overlapping issues. So that's what I got involved in.

I started a program called the Family Health Project. And in the Family Health Project, we started talking about issues. For example, somebody had AIDS and you got a pantry bag. If you had AIDS and you went to the food pantry or to the local free food bank, and you were a mother and you had AIDS. You could get a pantry bag just for some food items for yourself. But if you had children, you had to cook for them. Instead of coming home with a bag from the food pantry just for yourself, you really needed to have food that you could cook for your whole family. It took a while for us to have convinced the New York City Council, the New York City Health Department, that yes, if you had a family and the whole family was affected by either the mother having AIDS or the father having AIDS or a baby being born with AIDS, you needed to talk about the family as a unit, not just the individual. So eventually we got New York City to have pantry bags that were family pantry bags.

-

We developed the program called APICHA, the Asian Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV and AIDS. When we finally developed that program, they were able then to take their various Asian staff and go to the health department and go to the Centers for Disease Control or go to the New York City Council or various places and say, “Look, we need to be able to have funds to give information about this disease in a language that people can understand.”

Once somebody learns that they have this particular disease and they are limited in income and go to a food pantry, you have to then explain to the food pantry that you have to give this family a bag that has enough rice, has enough beans, has enough tomato cans of whatever that this family—this mother can continue to cook for her family. But she can cook food that is not only something that centuries of families coming from Asia or Africa or Europe—that people can eat the same food that their ancestral background has taught them. But also, it helps them with the disease which has symptoms or which has problems. And so we had a few families that at first, we not only had to get them to go to the doctor, to get the test and give the blood to find out why they weren't feeling well. And slowly but surely, we were able to get families to do that.

-

You can't imagine how many times you have to go to the City Council, the health department or the mayor's office or somebody to listen to the fact that this is a problem that needs to be solved. And when you have people who didn't learn anything about AIDS when they were in school, didn't learn anything about AIDS when they became a city council member, you had to start all over again and teach people about the disease, teach people about the transmission, teach people how various different languages affected different groups.