In this post, current OHMA student Yutong Wang (2016) discusses her perspectives on being a historian and how politics influence historical revisionism. This article is the second in a three-part series exploring Dr. Leslie Robertson’s recent OHMA Workshop Series lecture, “Devalued Subjectivities: Disciplines, Voices and Publics.”

As an oral historian, I believe that my crucial responsibilities are to be objective and communicate the context fairly when using narrators’ stories. Yet, sometimes this balance can be difficult to achieve in the process of completing a project and uncovering history.

In my own work, thinking about how to represent and combine content from multiple interviews has been a struggle because even a little modification in the process of editing can make the meaning very different. Dr. Leslie Robertson’s work navigates these considerations and goes further even by engaging with the very tradition of academic disciplines like anthropology.

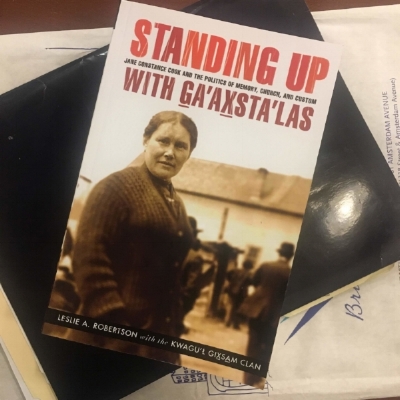

Robertson—a Canadian who was raised in Australia—is a researcher, a cultural anthropologist, and a professor at the University of British Columbia. She is also a co-author of an oral history-oriented book, Standing up with Ga’axsta’las: Jane Constance Cook and the Politics of Memory, Church, and Custom.

During her recent OHMA Workshop Series appearance, Dr. Robertson framed her lecture with this question: “How do disciplinary politics promote the reproduction and valorization of particular voices while (implicitly) devaluing others?” Robertson’s work invoked me to think about another struggle for many scholars in world, which is the political influence on historical records.

Jane Constance Cook (1870-1951), also known as Ga’axsta’las, was a leader and an activist among the Kwakwaka’wakw, some of the original inhabitants in the Pacific Northwest coast area of Canada. She was famous for supporting the banning of the potlatch, one of the most significant traditions in Kwakwaka’wakw culture.

Potlatch is a legal ceremonial practice to celebrate or commemorate important events such as marriage, birth, and new leadership. It is a method for people to prove their wealth and social status by providing a feast, performing, giving out or exchanging gifts, and even (most famously) destroying their own property. The tradition was banned by Canadian government in the Indian Act from 1885 to 1951 in order to better assimilate the area’s residents.

Because she supported the potlatch ban, Jane Constance Cook was regarded as a betrayer and a “colonial collaborator” by some Kwakwaka’wakw, which left her family excluded and isolated from the community. In order to reform the image of Cook and to reconcile with their own kind, Cook’s grandchildren invited Robertson to research and to write a biography of her.

This made me think: what is the image of Cook and how she is recorded among the Kwakwaka’wakw? Is it objective or biased due to their culture? And what do Canadian history books say?

This reminds me of one controversial phenomenon worldwide: historical revisionism under political power—or even negationism, the denial of the reality of well-documented historical events. Many countries modify their history textbook and limit the academic environment for historians, to serve political purpose. Some famous examples are: U.S. President George W. Bush and Iraq War, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, or Japan and the Nanjing Massacre in China. As a Chinese person who spent my early life in China, I also experienced Chinese historical revisionism.

After World War II and the collaboration of the two parties in China, there was a fight for leadership between Chinese communists and the nationalist Kuomintang. In 1949, the founding of the People’s Republic of China marked the success of the communists, while the Kuomintang moved to Taiwan in defeat.

For years in Mainland China, the contributions of the Kuomintang and its leader of that time (Jieshi Jiang) until WWII were barely mentioned in history textbooks and were even depicted in negative way in many TV shows. China has also blocked Google, Facebook, and Twitter, the three most powerful information exchange platforms in the world.

All these factors helped to mislead many people’s impression and knowledge about the Kuomintang in Mainland China because the government controls most of the information, education, media, and published work. After I came to America, I found that historical records in Taiwan and here are so different, describing the Kuomintang in WWII as the main power rather than the Chinese communists.

I now understand that the young Chinese government was trying to stabilize the country and in order to avoid fights between parties, eulogizing Chinese communists and disparaging the Kuomintang might have made it easier to earn the trust of the citizens and become more stable. But it would teach misleading or incorrect information to the future generations, and create restrictive academic environment for historians to discover and tell the history.

Although historians can’t control the governments of the world, we can minimize their political influence and try our best to conduct, present, and reserve our projects fairly. Objective and diverse historical records from worldwide researchers and scholars can together create a better environment to discover the truth.

To learn more about Dr. Robertson’s collaborative work, check out her book co-authored with the Kwagu'l Gixsam Clan: Standing Up with Ga’axsta’las: Jane Constance Cook and the Politics of Memory, Church and Custom.

Yutong Wang is an international student from Shenzhen, China, who holds a B.A.in Strategy Communication from the Ohio State University. Her project this year in OHMA is about Chinese students who study in America. By hearing the stories of these students, she wants to discover how their experience studying and living in the United States reshape their values and perspective of themselves and of the world.