Catherine Kirkpatrick is an award-winning photographer and writer based in New York City. In this post, she shows how oral history training has informed her projects as an archivist for Professional Women Photographers.

In 2009, after seven years of caring for my elderly father, I joined the board of Professional Women Photographers ("PWP"). As with many women, family demands had taken me from the workplace, and I thought this would be a great way to ease back in. I became their archivist, which seemed a good fit with my graphic arts and writing background. The group wanted to raise its profile, and incorporating its history into publicity material seemed a great way to go.

But visiting the unit, I overwhelmed. Instead of images, there were boxes and boxes of correspondence, yellowing files, magazine and newsletter drafts put together with tape and glue. Graphics were primitive, photographs small and nearly always black and white. The few slides I came across had faded to pale cyan. For a digital person, it was sobering.

Yet I also had a sense of history. Though notes and letters, exhibition cards and publications, you could track, on a micro level, the tremendous change that had taken place in photography over the past forty years. Women fought their way into the male-dominated field. Cameras and printers went digital, presenting stiff learning curves many photographers could not master. Film labs disappeared, as did many mid-level corporate jobs, which were now handled in-house, often by an intern with a good DSLR camera. Suddenly everyone had a camera, then a camera on their phone. Photography became commonplace, yet at the same time, rose to new heights in the art world. A significant market developed and prices were substantial. Shown alongside paintings in elite galleries and museums, the medium had arrived.

Documents of Professional Women Photographers

Yet in the rush to embrace new technology and opportunities, doors to the past had been slammed shut. There seemed to be two different worlds: a “before" and “after.” I was fascinated by the change, but even more by the people who had lived through it. Behind the economics and rapidly evolving tech, were many very human stories. Some photographers adapted easily, others were left behind. I wanted to understand and record their experiences, but wasn’t sure how. I wasn’t a journalist or historian, and felt others didn’t understand the significance of the voices and memories I heard. Perhaps the story wasn’t big enough or important enough, perhaps connections between the parts and players were not clear.

Documents of Professional Women Photographers

The idea of an oral history began to take shape in my mind. I joined the Columbia Center for Oral History Research (CCOHR) listserv, and began attending events. I heard the memories of coal miners in Kentucky and sanitation workers in New York. Each project underscored the fact that we are all witnesses to history, that individual voices matter. It caught my imagination, bringing eras and events to life in a way that text alone could not. There was a wide range of projects, and respect for many different cultures and people.

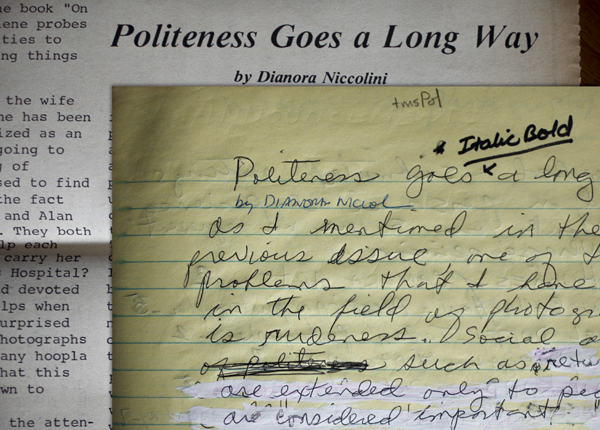

Inspired, I began interviewing women photographers who came of age in the 1960s and 70s, learning from their experiences about the barriers women faced. Despite a stellar photo education, Dianora Niccolini began her career sweeping up after men in the darkroom. To find a publisher for her ground breaking book, “Women Photograph Men,” Dannielle Hayes projected images from the back of a truck in Rockefeller Center till she caught the attention of an editor at William Morrow.

Photographer Dianora Niccolini ©C Kirkpatrick

I began to understand in a visceral way why so many grassroots arts organizations had been formed in the 1970s: it was the only way people shut out due to gender and race could find a place for their work and ideas. Many opportunities enjoyed today were paid for by their struggles. Some are gone, far too many have been forgotten. Like the vibrant Yiddish theater scene that flourished along 2nd Avenue in the early 20th Century, the small, quirky photo world of the 1970s, with fixtures like the Floating Foundation of Photography (purple barge, Hudson River) had vanished.

Birthday Self Portrait ©Meryl Meisler

As I listened and learned, the scope of the project grew. It was a large story, with many fascinating strands, intertwined and ever compelling. The talks at CCOHR inspired me to begin, and workshops with Gerry Albarelli (Oral History for Writers) and Marie Scatena (Oral History in Museums), gave me the courage to continue, confirming what I suspected–that individual voices matter and enrich the larger weave of history. Each step–interviewing, recording, blogging–became a dialogue with the photo community and photo history, drawing me deeper into the project. Will it be a pure oral history? Probably not. But whatever the final shape, it will be better for exposure to the discipline, which has touched in deep ways many other aspects of my creative life.

Read Catherine's blog posts for PWP.

Check out her series 30 By 30, where women photographers talked about the women photographers who inspired them.