Jonathon Fairhead is a current OHMA student. In this post, he discusses whether or not Moustafa Bayoumi's encounters with Muslim Arab Americans are oral history.

I remember in the years after 9/11 when reports of torture and the abuse of detainees at the hands of American forces abroad began to filter in through the media, a writing teacher saying something along the lines that if one were to squint everything in the country could almost look alright. Reading Moustafa Bayoumi's accounts of Muslim New Yorkers experiences being detained without trial or recourse to legal protections in the aftermath of 9/11 forces one to look straight at the reality of how many Muslims – possibly more than we will ever know – were treated simply for being Muslim in New York in the aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Bayoumi's encounters with his subjects are intimate. As a Muslim New Yorker from a cosmopolitan background – he is the child of academics, was raised in Switzerland and educated in the United States – he is an insider, able to connect with his interviewees from a place of shared experience. The sense of trust between him and his interviewees is palpable: often they are speaking of experiences previously unspoken beyond the confines of family and community, injecting into the landscape of the American experience their first-hand experiences of detainment and surveillance. An example of his insider status that he shares with workshop participants is an account of an eponymous fictional character named Moustafa Bayoumi that he happened across on the internet one night. That Moustafa Bouyami, also the child of academics, is a Muslim killer terrorizing the godly in Europe.

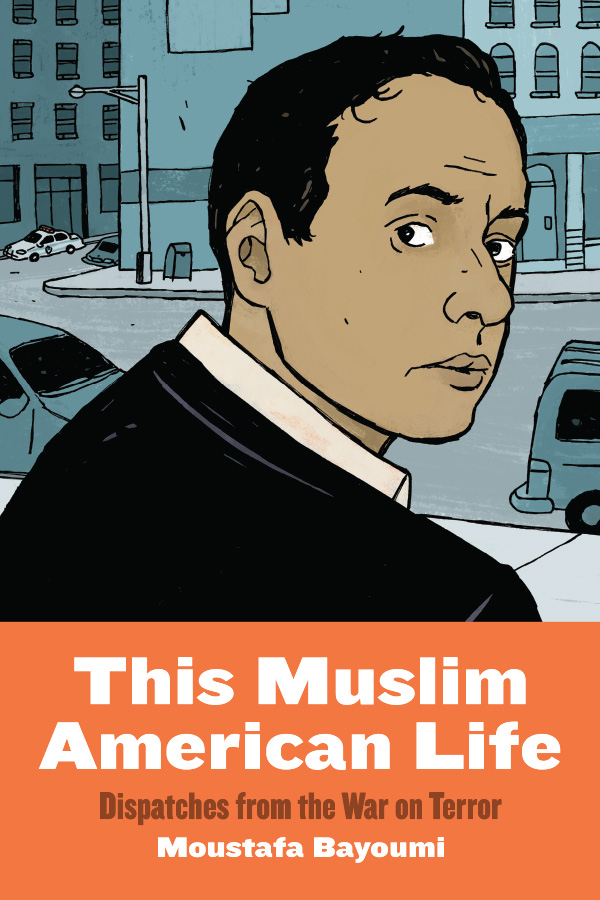

The narrative we studied in advance of the discussion with Bayoumi and the students of the Oral History Master of Arts program at Columbia forces us to adjust our gaze and look directly at the experience of Rasha, a young Muslim teenager living with her family in New York in the aftermath of 9/11 when her home is raided by the FBI in the middle of night. Her younger siblings being born in the United States are not imprisoned, but she, her mother, father, and brother – all born abroad – find themselves caught in a legal twilight zone as they are imprisoned for months without any recourse to any rights under US immigration law. Bayoumi's account of Rasha's experience has been published in his collection This Muslim American Life and also as a stand-alone piece in New York Magazine. The audience of oral historians at Bayoumi's Columbia talk choose to interrogate the technical aspects of his method as much as his views on the state of the nation, orientalism (he was student of Edward Said) and the details behind the narratives.

I ask if he considers himself an oral historian and he says no. He says he does the work he does in order to understand the experiences of the people whose experiences he recounts, a quality he surely shares with most oral historians as well. The conversation reveals, however, that he is less interested in the process of meaning making for which oral history is known. He has a journalist's tenacity for fact checking and will confirm the events and timings of his narratives against known sources. He corrects vagaries of memories instead of being fascinated by them, a trait that could be said to place him more firmly in the journalistic camp. He spends considerable time with his interviewees, studying their lives and communities before committing to a recorded interview. It is from these interactions and the recorded interview that he crafts the moving works of creative non-fiction for which he has become renowned and which have garnered him the attention of oral historians and lead to his presence here at the workshop. One can surmise that it is oral historians reaching towards him as one of our own more than him reaching towards our roomy embrace. Another detail that separates him further from standards of oral history practice is the fact that his recorded interviews live, presumably without duplicate, in a box in his Brooklyn home. With the zeal of oral historians for historical preservation the workshop participants encouraged him to archive post-haste and suggested archives like the one at Columbia or the Brooklyn Historical Society.