Mario Alvarez is a current OHMA student. In this post, he discusses the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project's multimedia approach as an example of effective public-facing oral history.

Manissa Maharawal, a doctoral candidate in the Anthropology Department at the City University of New York, spoke to us about The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project. This project is the work of a collective that seeks to document the stories of those dispossessed as a result of gentrification in San Francisco and the Bay Area. It achieves this primarily through the use of maps, each of which highlights a different mechanism of gentrification in this city (one depicts each instance of a landlord buyout in San Francisco, for example). The centerpiece of these maps is arguably the Narratives of Displacement – Oral History Map. I found it to be a startling fusion of data visualization and oral history. This map – and particularly the mural project borne out of it – is an instructive example of how oral history can be woven into a larger work.

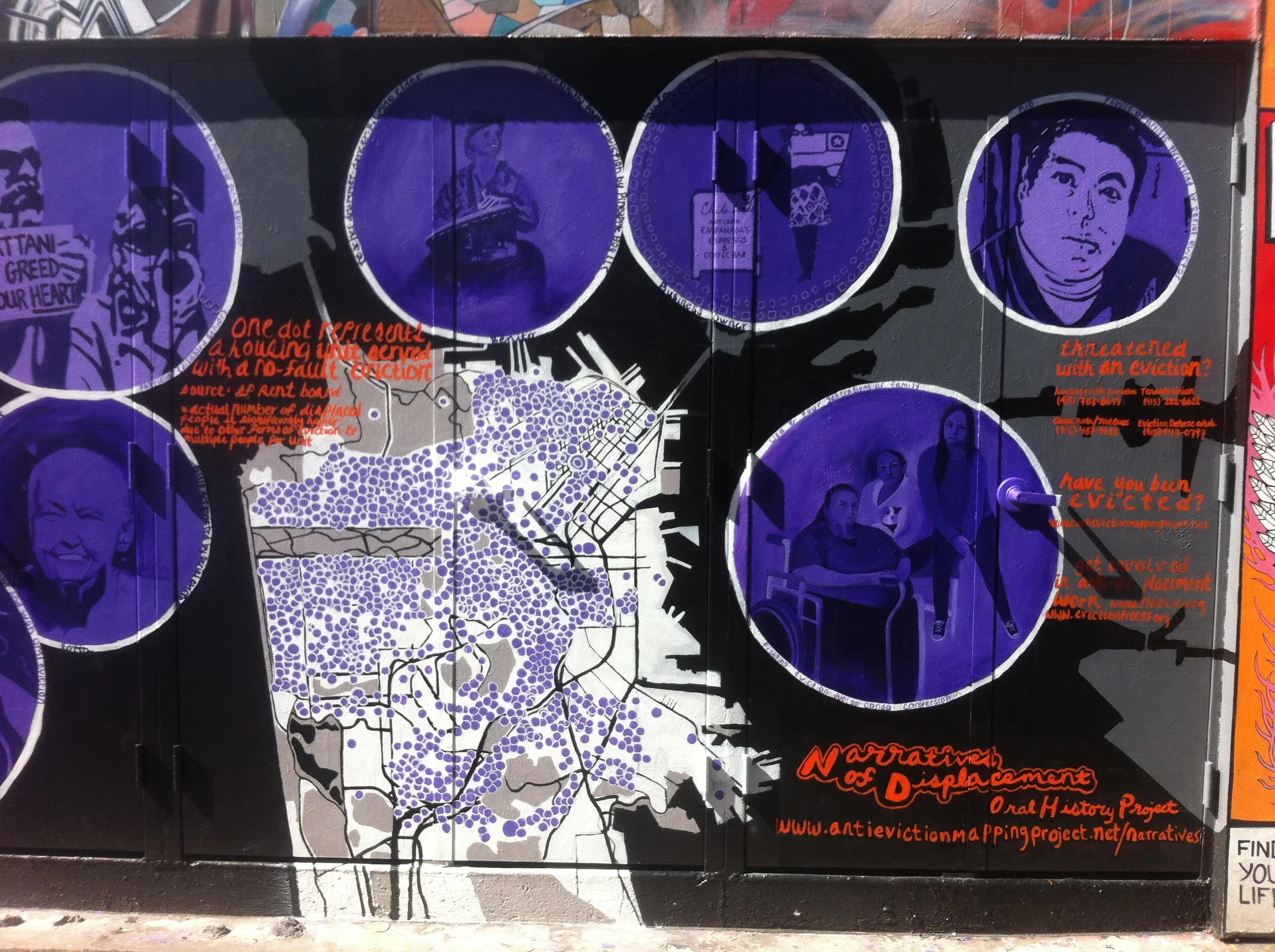

On the Narratives of Displacement map, there are over 12,000 red dots that represent each instance of no-fault eviction in San Francisco from 1997 to 2014. About forty of these dots, however, are colored blue to indicate that there is an oral history of the tenant who faced the eviction available. The subjects of these interviews, who range from artists, to activists, and to teachers (and sometimes are all three), each have a unique life story to tell through the lens of their eviction experience. These narratives add a personal element to a phenomenon whose scope has the potential to be dehumanizing, and thus lends this map a visceral quality that I’m not sure would be there with just the dots alone.

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project is very much interested in providing these narratives to the public and therefore sought to go beyond the limits of the already exhaustive interactive map. By working in tandem with the Clarion Alley Mural Project, AEMP was able to put up a 20-foot mural in San Francisco’s Mission district. The mural is bright and full of contrast: shades of purple and black ensure that the piece stands out in Clarion Alley. This painting presents the stories of eight tenants who, in the face of some daunting odds, won their eviction fights. There is a portrait for each subject, each of which is framed by a white border in which the subject of these stories signed their names. A phone number is listed for passersby interested in hearing these individuals’ oral histories. These elements, both audial and visual, combine for a comprehensive project that demands the attention of anyone who happens to walk by.

One notable story was that of Tom Rapp and Patricia Kerman, a maintenance technician and a disabled senior citizen who were roommates in a flat in the Mission district. The two were able to overturn their eviction with the aid of organizations such as AEMP. They tell their story in this video of the mural’s grand opening, which you can see below:

The opening of the mural was a great example of how oral history can honor subjects through the power of collaboration. Note how much time is given to the people depicted in the mural – they essentially have center stage for the entirety of the event. They have an uncommon opportunity to tell their story to a sizable and engaged audience, not merely to the interviewer in an isolated, soundproofed room. It is a rare treat to see a project that incorporates oral history doing this so in such a public forum.

The question of how to make our discipline more accessible to a public audience has always served as somewhat of a challenging one, and I think the mural could be a model for public-facing projects going forward. It is simply not enough to make already existing oral history archives available to a wide audience. In undertaking a project, particularly ones that focus on an oppressed or underserved set of people, one should consider ways to collaborate with subjects beyond the few hours that they are being interviewed.

Like all murals that are part of the Clarion Alley project, AEMP’s piece has since been painted over. In the time that it was on display, however, this multimedia project reached potentially thousands of spectators who never would have gone to an archive. I was heartened to see AEMP’s efforts to reach out in such an unorthodox way, and hope future oral history projects are this engaging with the communities in which they take place.