In this article, Fanny García (2016) reflects on her process as she worked to create an oral history exhibit for Inside Voices: An Oral History Exhibition in April 2017. She writes that she believes strongly in the decolonization of cultural spaces and in the creation of exhibits and installations that mobilize people to action.

During the exhibit, my pitch to the audience was this: “The idea for this exhibit is to take refugee stories out of the media headlines and to place them in a space that is representative of every day life. As such, I’ve recreated the dwelling spaces that refugees leave behind when they are forced to flee their homes. What you’ll find in this exhibit are spaces that have been recreated based on the memories and photographs provided by the narrator of her home in El Salvador. You will start at the garden; move into the living room and around the corner into the dining room. Interspersed throughout these three spaces, you will hear a different part of the narrator’s story. You will also find objects of memory that the narrator either carried with her on her journey to the United States or that she left behind when she escaped.”

My goal was to create an immersive experience, one in which an individual could experience the life of a person who has been through extreme hardship, in a setting that is familiar and comforting. Primarily, I wanted the audience to feel as though they were having a conversation with a friend.

For the exhibit, I had a 10 ft x 10 ft space available to me in the Social Hall of Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan, New York. The seminary, known as the "birthplace" of Black Theology and Womanist Theology, still only has portraits of White men (save one woman, also White) displayed on the walls of the hall. It wasn't until 2008 that feminist theologian Serene Jones became the seminary's first female president in its 172-year history.

Below are photos of the space before the exhibit:

As soon as I saw it, I knew the space needed to be transformed, so I turned to Professor Jack Tchen's work. He spoke during one of OHMA's Thursday Workshops about decolonizing public spaces in Manhattan, New York. His article, Who is Curating What, Why? Towards a More Critical Commoning Praxis argues that curatorial practices remain mired in Eurocentric traditions and must change and take into account the postcolonial world. He writes that the terms curator, curating, and curation share the Latin root cura, which means, “to care” and that over time the term has become institutionalized and now represents a person who is in charge of a museum or collection. As such, curatorial work until today has never been free of colonial and imperialist “formulations of knowledge, selection, and power.” Tchen believes in the decolonization of museums, exhibit spaces, and curatorial work and insists that contemporary curators must be “shape-shifters” who wear multiple hats to engage in various practices and discourses at the same time. These practices include literature, ethnography, cultural anthropology, oral history, storytelling, and multimedia art and film. During the workshop at OHMA, Tchen reiterated, “You can’t just show, you have to also be able to move people.” If you make them care, he said, you may get them to mobilize.

I had to see for myself just what Prof. Tchen was talking about so I traveled to the Museum of Chinese in America, a museum he co-founded in 1980 to preserve and present the history, heritage, culture, and diverse experiences of people of Chinese descent in the United States. Together with my classmate and friend Xiaoyan Li, we explored the museum’s core exhibit, “With a Single Step: Stories in the Making of America.” The exhibit presents the complex and diverse experiences of Chinese Americans and intertwines the historical and political contexts of Chinese migration to the United States. The curation of the exhibit focused on the use of personal stories and cultural objects belonging to multiple generations to review three main aspects of this history:

1.) The relationship between China and the United States; and the impact this relation has had on Chinese Americans.

2.) How Chinese Americans have perceived themselves in American society and how others have perceived them over time.

3.) The impact of Chinese Americans on American politics, culture, and life.

Fanny García looking up a wall of documents featured in the “Down With Monopolies! The Chinese Must Go! (1870 – 1930s)” section of the core exhibit at the Museum of Chinese in America.

The section of the exhibit that completely mesmerized and intrigued me was a wall onto which official government documents had been arranged. These documents were letters, identification cards, birth certificates, and other paperwork, which were generated by Chinese Americans to prove American citizenship after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882. On the other side of this wall were wooden panels from Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay which starting in 1910 functioned as an immigration detention center. Chinese immigrants detained on Angel Island had carved their names, poems, and messages onto these wooden panels and in present day 2017, I stood transfixed by the stories these objects told — stories about having to prove that you belong in the United States, and the need to leave a mark to signify that you exist and that you matter. Most importantly however, these documents and objects tell the story about how U.S. immigration policies impact individual lives.

And so let me return to the pitch I made to each audience member when they walked into the exhibit for Inside Voices: An Oral History Exhibition. What I tried to recreate was a moment that in a sense, forced people to experience a refugee woman’s life through objects and memory. I borrowed personal objects from my narrator to trace the stories within the main story of migration and displacement to also highlight her decision-making and survival instinct. As such, the space needed to be transformed into a dwelling that could absorb, not just display, my narrator's memories and personhood.

An ankle fracture earlier in the year had me hobbling around on crutches so I knew I needed to use the furniture already housed in the social hall. This included a sofa, four chairs, and a table. From home, I used a coffee table, and a decorative table for the garden area which also included enlarged photographs of the narrator's garden. My narrator provided objects of memory including a letter that her daughter had written to her while they were both detained at the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas. This and other photos were framed and displayed throughout the exhibit. The garden area specifically held a lot of memories for the narrator, specifically the care she gave to the hydrangeas in the patio of her house in El Salvador. I found a nice shrub of purple hydrangeas at my local florist shop which my narrator took with her after the exhibit.

One of the walls in my 10 x 10 space included a built-in bookshelf so I used white poster board to create a TV and entertainment center for the living room area. Family photos with faces blurred to protect my neighbor's identity were arranged on the shelves. The book my narrator's daughter carried from El Salvador to the U.S. was placed in the center of a crocheted doily on the coffee table - a slideshow of my narrator's hands played on the makeshift TV. Audience members sat on the sofa and played an audio clip of my narrator discussing her feelings on motherhood from two iPads that were made available.

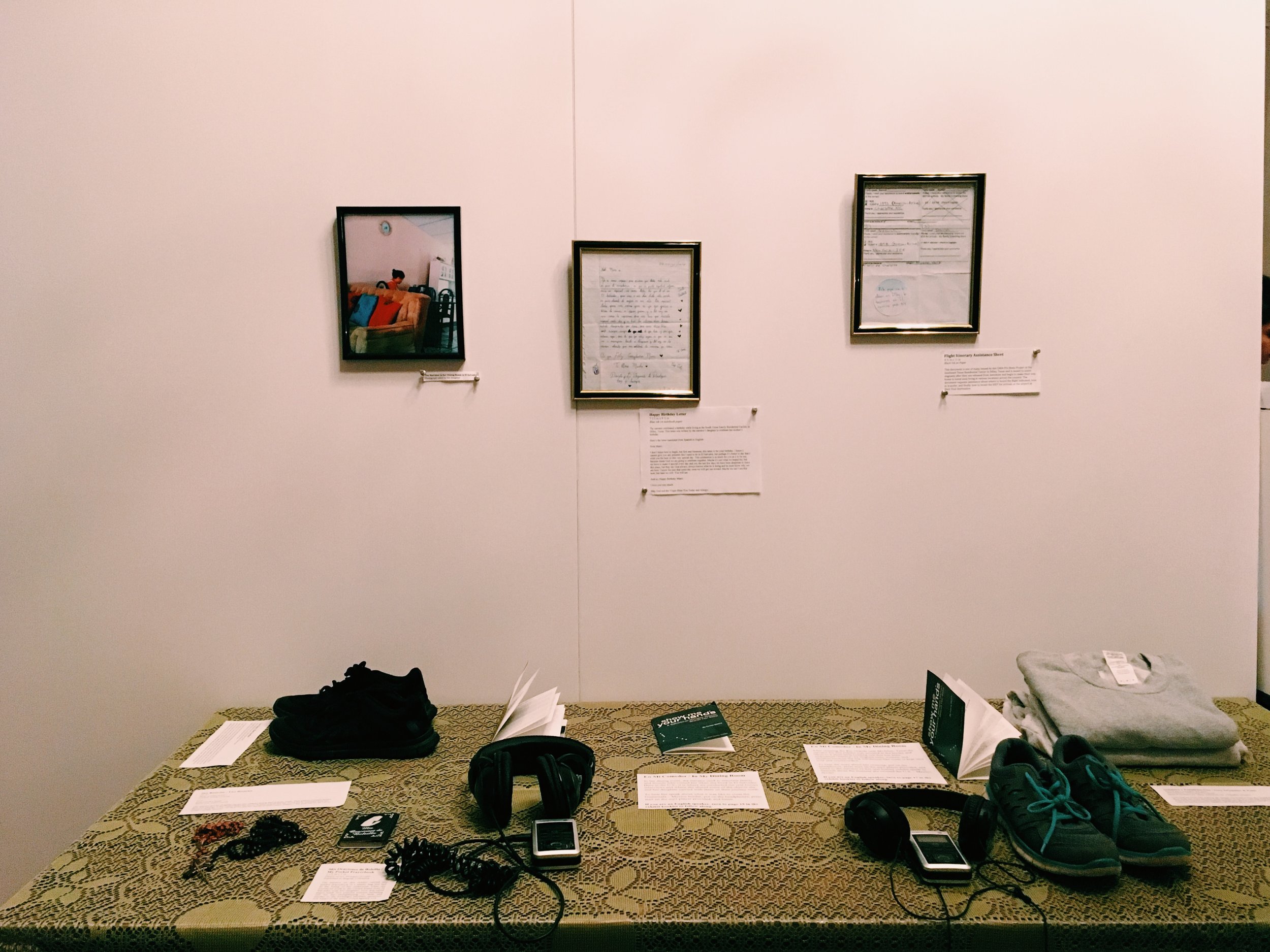

The OHMA program provided a 4 ft x 8 ft v-flat that I used as a dividing wall between the living room and dining area. The dining table was covered with a green lace tablecloth and displayed on top of it were various objects my narrator carried with her on her 2,000 mile journey from El Salvador. Among other items, this display included two rosaries, a Catholic prayer book and the shoes she was issued in the detention center. In both the garden area and the dining room, audience members could listen to another section of the narrator's story on MP3 players and headsets.

Below are photos of the space during the exhibit:

Finally, by publishing a booklet, a catalog of sorts for the exhibit, I was able to put the narrator’s migration journey into a transnational context that emphasizes the impact that United States foreign policy and increased militarization has had on El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. The exhibit booklet served as a guide for the exhibit but also provided the narrator’s story in English since the oral history interviews were all conducted in Spanish. I did this after my exhibit mentor; Nyssa Chow advised me that an exhibit must be self-explanatory and that as soon as someone enters the room they must have a sense about what is happening. The booklet served as a "literary passport" through the exhibit, one which each person could look through to seek answers to any questions that might arise during their time in the space.

Lastly, I wanted the exhibit to stay with the audience long after they left the social hall. And so I hope that while on the train, or at home when they emptied their exhibit or conference swag bag, they pulled out the Show Me Your Hands booklet and read through it to learn more about the Central American Refugee Crisis.

Fanny Julissa García is a recent graduate of the Oral History Master of Arts program at Columbia University. Her research focuses on the Central American Refugee Crisis and the rise of immigration detention centers in the U.S. She currently works as a social media marketing content writer for various organizations including Groundswell: Oral History for Social Change, the Columbia Oral History Master of Arts program, and the CCOHR 2017 Oral History Summer Institute.