How should educators navigate controversial issues like war in their lesson plans? Current OHMA student and veterans’ oral historian Elizabeth Jefimova offers a few tips for educators looking to incorporate the topic of war into their curriculum and how oral history methodology provides a unique solution in teaching war.

Throughout my time as a student, the subject of war has always been placed on a strict timeline. As students, we learn to navigate the subject of war through a series of important dates and achievements that ends once victory or defeat is claimed. Most history curricula approach war through this myopic lens, which is supported by a mainstream academia that does not incorporate the multiple intricacies and meanings of war that are felt by its participants. In this year’s winter workshop event, “The War Is Not A Bomber Jet Anymore”: Reencountering the Korean War through Aural History, Professor Crystal Mun-hye Baik and members of Nodutdol for Korean Community Development considered the need to redress how the Korean War is remembered and the intergenerational silence that the war produced in thousands of Korean families. Long termed the “The Forgotten War,” because of its existence between the hot-buttons of World War II and the Vietnam War, the Korean War still produces a visceral reaction from most Korean families and those who served during the war. In American textbooks, the war is deconstructed into three years of history, 1950-53, but the Korean War only officially ended in 2018. “The War Is Not A Bomber Jet Anymore” event raised an important question: How do we teach war to younger generations?

Nodutdol’s example focused on connecting the experiences of elders and the younger adult generation, the 20- and 30-somethings. But what about our youngest? How do we teach war to elementary and middle school kids? Is there a way of approaching such history that is content-age appropriate without sanitizing to the point of reproducing narratives that are ultimately oppressive and harmful?

We want students to act like detectives as they navigate this nation’s history. We want them to be inquisitive and engage in critical thinking. However, we also want to ensure that young students, specifically those in elementary or middle school, aren’t exposed to material that they either cannot emotionally handle or is considered inappropriate for their age.

Incorporating my oral history experience interviewing veterans, I want to use this space to present a short preliminary guide for educators who might be preparing a curriculum for younger children that centers around war, and show how oral history might be a useful tool for them to maneuver some of the more difficult elements of history into an effective lesson and conversation.

FIND OUT WHAT YOUR STUDENTS ALREADY KNOW ABOUT WAR

Before constructing a curriculum that centers around war, educators should keep in mind what they want their students to get out of this experience. One way of figuring out your end goal is to incorporate the 10- Point Model, a list of “points” that educators should incorporate into their lesson plans if they will be teaching controversial topics. To start, survey the students. They are probably coming in with their own perspectives and definitions of war, especially when most younger generations were born into the era of the “War on Terror.” Assign a homework task that gauges students’ knowledge and perceptions of war. Find common definitions or points of misconception, and find areas where your students’ answers differ. Use this survey to create a lesson plan that addresses where the students are coming from and sets a reasonable goal for what you want them to get out of the lesson.

USE DIFFERENT MEDIUMS FOR ENGAGEMENT

Just as it is important to consider the different perspectives that students might bring into the classroom, it is important to use different instructional mediums to address generations that are born into a more technological, fast-paced world. Try to embrace that affinity and leverage it for learning. One solution? Oral history. I know what you must be thinking: “Oral history is the exact opposite of fast-paced!” But one of the primary tools every oral historian uses is a recorder, a now-digital technology. Have students become acquainted with the device and as an initial assignment have them interview each other. Once they are comfortable enough, bring in speakers or those who were impacted by war. By having children interview the guests, they are actively engaging in the conversation and are thus able to absorb information at their own pace. A wonderful example of this is found on the Youtube channel, Hiho Kids, where kids were able to speak with veterans, Holocaust survivors, Japanese-American internment camp survivors, and more. Depending on the grade level that students are in, the narrator and teacher should work together to identify a boundary about what is age-appropriate to share with the students. The interview, semi-structured but still spontaneous, will expose kids to ethical dilemmas but in a more healthy environment, and it would provide an intergenerational conversation for both parties to learn from.

AFTERCARE

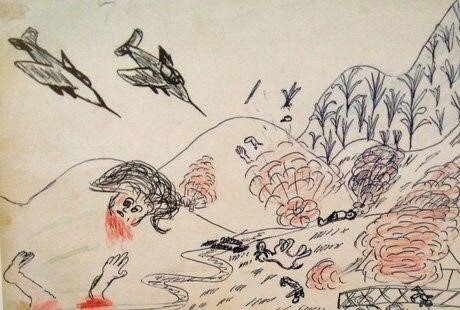

Children absorb information differently. As oral historians we know the importance of self-care after listening to material that may be stressful. If educators are responsible for how children learn, then they are also responsible for how children deal with such information after class. Create an art workshop. Have students incorporate what they learned with art projects. Providing a creative outlet that is still tied to the lesson can help students. This can be done with the guest speakers so after students sit and interview them, everyone can switch to a more relaxed medium to process everything that happened so far.

As someone who has sat with and interviewed veterans who’ve experienced intense trauma and PTSD (sometimes diagnosed, sometimes not), I’ve come to know that learning about the history and impact of war is not about listening to particular stories, or getting all the harrowing details. It is about piecing together moments of personal truth and contextualizing them with narratives that don’t incorporate the whole story. Kids can learn and process history through the internalized connections they make with narrators if educators incorporate oral history methodology into early classroom settings.

It is time for educators to rethink old practices and foster a new era of young historians.

Photo Credits:

[1] Aguilar, Elena. "Teaching Children About the Brutality of War." Edutopia. July 17, 2013. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/teaching-children-about-brutality-of-war-elena-aguilar

Elizabeth Jefimova will be graduating from OHMA in Spring 2021. Her graduate thesis revolves around documenting student veteran experience and examining the challenges that post-service transitioning can contribute to in a veterans’ pursuit for higher education. Currently, she is a writing intern with the Department of Veteran Affairs and a co-producer for an upcoming podcast highlighting Native American military service.