Intro: Nishani Frazier, educator, black freedom scholar, and someone unafraid to turn oral history practices on their head, recently returned to Columbia (where she earned her PhD) to discuss "The Sounds of Blackness: Space and Sound Preservation as Oral History Advocacy."

In anticipation of Nishani Frazier's presentation at Knox Hall during the OHMA Spring Workshop Series we, as students and interlocutors, were assigned readings which included the preface to her book, Harambee City: The Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism. Frazier had me hooked with her response to queries about her scholarly detachment (was she too close to her sources?) and to questions she faced regarding the validity of her subject and methodological choices. As a scholar and oral historian, I was energized by her succinct review and analysis of structural power, her focus on transparency, authority, and exclusion, and the wonderful convergence she illustrates of the shared values in the ideologies of social justice and oral history. I was excited for this presentation and the nuggets of brilliance that were sure to shine forth!

Frazier started the evening by speaking to the OHMA class about the development of her Harambee City project, the interactive website that she developed out of her book. Working with a skilled team at Miami University's Center for Digital Scholarship, Frazier has created a resource of maps, articles, interviews, and lesson plans on the site and has also included, in a practice of transparency and shared power, her reasoning behind design decisions as well as opportunities for users to talk back. Even as a work in progress, with a tab entitled “Updates & Under Construction,” this is an exciting pedagogical tool. Here Frazier delivers an example of how oral historians might contribute their work to digital archives, public history, and/or sites of interactive learning. As she stressed to the class, our work after developing knowledge continues with its dissemination.

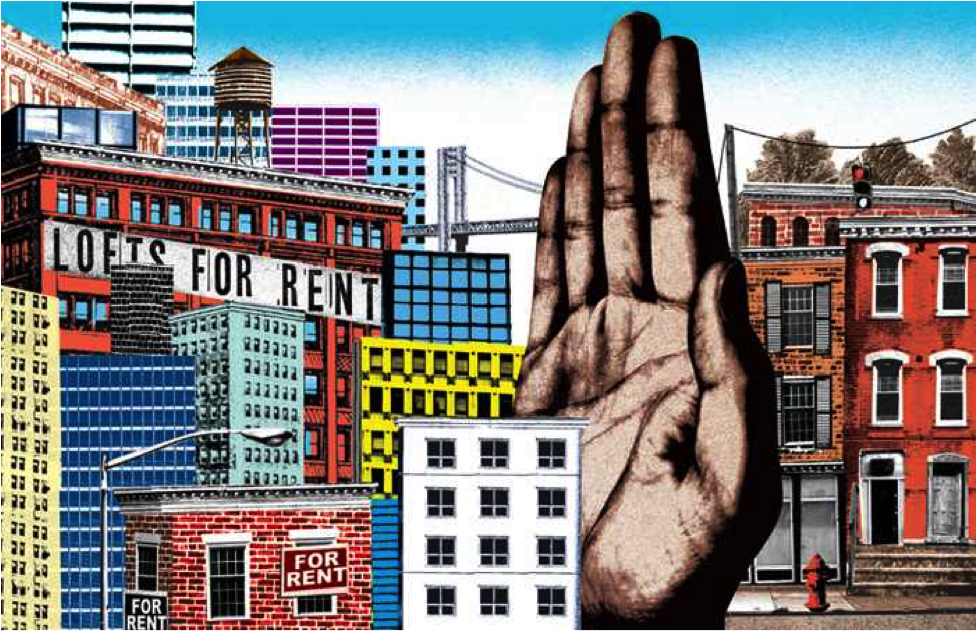

With that in mind, her current project is being designed to facilitate both knowledge production and distribution. Frazier told us that while chronicling the alarming changes in her father’s neighborhood in Durham, NC, she noticed that although gentrification was happening across the country, there were few, if any, national associations for documenting and fighting the practice. With funding from the Institute of the Black World 21st Century (IBW 21), Frazier joined with Professor Zachery Williams to create the National Gentrification Project, a digital database and resource center on and against gentrification. This hub, as Frazier referred to it, is still in its nascent stage. Her talk deconstructed gentrification, as a concept, and illuminated how we can contribute to fighting it.

Frazier’s analysis dives beneath the palatable descriptions of economic development and neighborhood revitalization that are used to frame scenarios of gentrification. She asks the probing questions of how can economic development and displacement co-exist; for whom is revitalization; and who is displaced if gentrification does not include affordable housing and integration? Where do the people who are pushed out go? What happens to the aural and visual memory of those who are displaced? More powerfully, Frazier asks and answers, what is the process of dispossession and how do we intervene?

Frazier argues that the framing and vocabulary of gentrification intentionally obscure the dispossession and erasure of marginalized, often poor (predominantly) people of color. While these strategies for displacement are varied in scope and impact, they start by attacking a neighborhood’s cohesiveness, by targeting cultural landmarks. Frazier reminds us that sight and sound are the tools that craft the memory landscape. By changing or removing the visual and aural markers of a community, the process of gentrification actually dismantles and erases the history and connective cultural tissue of vulnerable communities allowing them to be more easily and invisibly displaced as part of an economic gain.

As oral historians we are uniquely skilled to participate in interventions. How? By making “place” the subject of the interview. We consider ourselves attentive listeners: adept at noticing and conveying powerful moments, incisive commentary, and the community connections within the stories of under-represented constituencies. What would it look like, then, or more appropriately sound like, if we interviewed a place? Go ahead, Frazier encourages us, disregard the first lessons of your training! Do not seek out a quiet, intimate location for your interview. Take your recording equipment out into the streets, to the local hub, the porch, the shop, the bar, the corner. Catch the evocative sounds that signify place: basketball down the street on Saturday mornings, rambunctious youth on their way home after school, music from cars as the night gets started, the wind through the poplar leaves up Carlton Avenue, dominoes on the stoop next door to Chavela's. As Nishani Frazier so forcefully wrapped up,

“How do you capture a neighborhood vibe?

How do you articulate the feeling of a place?

How can you save the sounds of blackness?

You give the whole of the people and the whole of the place a platform to speak.”

With the warm weather coming, why not check your equipment, make sure you have fresh batteries, and head out into the street?

Check out this brief video from UC Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project on some of the strategies of gentrification that Nishani Frazier discussed.

Valerie Fendt is a second year OHMA student whose other job involves the digitization of Columbia’s Time Based Media archive. She is interested in the liberatory potential of education and often finds herself asking “but who is the archive for?”